This is a common question asked by many homeowners every year as fall turns into winter and the temperatures drop. More often than not, it is asked by people with homes that are less than 20 years old, or by people with homes that are much older with newly installed windows. While the simple answer would be to just blame the windows, it is actually much more complicated than that.

Have you ever had an ice-cold glass of lemonade outside on a warm, humid day? Did you notice how the outside of the glass accumulated moisture? The reason that the water collected on the outside of the glass has everything to do with the dew point.

For those of you that are not meteorologists, Wikipedia defines the dew point as “the temperature below which the water vapor in a volume of humid air at a constant barometric pressure will condense into liquid water.” The simple way to think of this is that any material (such as the glass in your windows) that has a surface temperature below the dew point (the temperature inside your house that will convert the water vapor in the surrounding air into solid water) will accumulate that solid water on its surface (remember the lemonade glass?).

“So what does this have to do with my windows?” you might ask.

When discussing window condensation with homeowners, I always tell them that there are two parts to solving their window moisture problems. One part is my job, and one part is their job.

The first part (my job) is to make sure that the home has windows with a high quality glass package that will keep that glass temperature as high as possible. It is important to set realistic expectations at this point. When the temperature outside is 0° and the inside temperature is 70°, it is unrealistic to expect your inside glass temperature to be 70°. Typically, depending on the quality of the window, the inside glass temperature will be somewhere between 30° and 55°. Obviously, the warmer it is, the better. This is important because, if that glass drops below the dew point, you will see moisture appear on the glass.

The second part (the homeowner’s job) is to control the humidity levels in the home in order to keep the dew point as low as possible. There are many sources of humidity in the home, including humidifiers, heating systems, cooking, showers and baths, plants, pets, and even our bodies. All of these things contribute to the amount of moisture in the air inside our homes. As newer homes have been built tighter with less air leakage, and older homes are being retrofitted with tighter energy efficient products, this moisture cannot escape to the outside like it used to be able to, trapping the moisture indoors and raising the indoor humidity levels higher than they were in the past. In addition, the type of window treatments that you have, as well as the placement of your furniture and plants can contribute to small ‘microclimates’ around your home in the areas of your windows. These are areas where humid air may get trapped near the windows creating a microclimate of higher humidity and colder glass surfaces that can be drastically different from an area only a few feet away.

So what can a homeowner do?

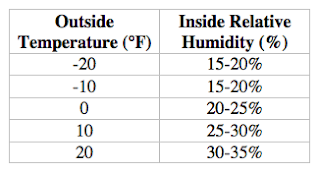

During the winter months, carefully monitor the humidity levels in the home. The following chart shows where your indoor humidity levels should be based on the outdoor air temperature. While some of the humidity levels may seem low and can contribute to static electricity, nasal and throat discomfort, and gaps in woodwork and floors, these are the ranges required to eliminate that moisture seen on the windows.

To do this, be sure to turn off any whole house humidifiers in the colder winter months. Another solution that has proven to be very effective is to use a heat recovery ventilator (HRV) to exchange the moist inside air with the dry outside air. These systems work by drawing the warm moist air from the house into the unit through your cold air returns, sending it to the outside of the home through a duct, and then drawing cool dry air from the outside back into the house to replace it. The cool air coming in passes by the warm air going out to warm it up to room temperature before it is blown back into your home. An HRV can be purchased from your local heating and cooling contractor, who will typically do the installation and adjustments required.

In addition to maintaining lower humidity levels, open any heavy curtains and move furniture away from windows that may block air circulation. Keep plants out of your bow and bay windows in the winter. Be sure to use an exhaust fan in any bath or shower areas to take the moisture outside of the home, because that moisture doesn’t just stay in the bathroom.

If all of this sounds like a lot of work, or if you like to have a little more humidity in the air than what is listed above, you should expect to see some moisture on your glass. If you have wood windows, you can expect this moisture to seep into the sash frames and damage the finish, rot the wood, or grow mold along the edge of the glass. However, if you have windows that are made of fiberglass or vinyl, this moisture will typically dry up once the weather outside warms up or the humidity level in the home drops, without causing damage to the finish or function of your window. Therefore, when considering your window choices, it is important to think about what the window frames are made of.

A Real World Example

My house was built in 2003 with a medium grade wood window installed by the builder. I purchased the home in 2004, and immediately noticed that, in the cold winter months, a large amount of moisture would develop on the bottom two inches of glass on every window. The window above the kitchen sink and the windows in the bathrooms would get even more moisture, and on really cold days, it would turn into ice.

I decided to change out the most problematic windows first and replace them with a fiberglass window. The window has an interior that can be stained to match real wood, but is completely unaffected by moisture. Within a few days of the new windows being installed (they were installed in February), the temperature dropped to around 0°F. My old windows showed the typical two inches of moisture on the bottom, and some of them were starting to freeze. My new window, installed only a few feet away on the same wall, showed about a quarter-inch of moisture just along the bottom edge. Obviously, I had raised the glass temperature by installing the new window (the glass temperature on my new window was 55° when measured two inches up from the bottom in the middle of the window, while the old windows were 42°).

This eliminated most of the problem, but the humidity levels in my home were still high (around 55%). My next step was to install an HRV to reduce my humidity and equalize it with the cold outside air. After the HRV was installed, I was able to reduce my humidity to around 35%, which completely eliminated the moisture on the new window and, after a few days of running it, also dried up the moisture on my old windows. However, the damage had already been done to the old wood windows, which showed black mildew and wood rot along the bottom edge of the window sash. The Infinity from Marvin Fiberglass window remained unaffected by any of the moisture.

So as you can see, there are two parts to solving window moisture problems. One part is my job, and one part is yours. Together we can work towards a successful outcome.

Mike Wood, Sales Manager

Leave a Reply